Taking a Bite from the Proverbial Apple: Intellectual Property for Attorneys and Entrepreneurs

WANT TO SEE MORE LIKE THIS?

Sign up to receive an alert for our latest articles on design and stuff that makes you go "Hmmm?"

What does it take to be a successful entrepreneur in the 21st century? Sure, it takes a smart idea, some start-up capital, angel investors, a venture capitalist or two, and that nonquantifiable bit of luck. You also need an innovator at the helm of your company who is willing to take risks. All of this is fairly well known.

However, there’s something else that is vital in order for a business to break away from the pack: a savvy attorney with a deep knowledge of intellectual property law. Accompanying that knowledge must be the acumen to recognize that effective use of intellectual property requires applying “design thinking.” Tim Brown, president and chief executive officer of IDEO, a leading global design firm, offers the following definition as a starting point: “Design thinking can be described as a discipline that uses the designer’s sensibility and methods to match people’s needs with what is technologically feasible and what a viable business strategy can convert into customer value and market opportunity.”[1]

Starting a business while being mindful of the juxtaposition of intellectual property and design thinking is no longer just another good idea, it has become essential. Many entrepreneurs underestimate the importance of protecting their intellectual property, and merely request that their attorneys help them register a trademark or two. Many are unaware of the effort required to actually brand a product in a way that generates excitement across generations and fosters customer loyalty. Entrepreneurs should think creatively about branding and innovation because sufficiently original branding is protectable through the various tools of intellectual property—trademarks, copyrights, trade secrets, and patents.

There is much to be learned from the way Steve Jobs and Apple created and aggressively enforced the company’s intellectual property rights. Apple did not become what it is today with only great innovators and good ideas. Apple has a high-quality legal team, with innovators and attorneys working together and willing to design an experience for consumers—an experience protected by a well-designed intellectual property package. By properly applying intellectual property and design thinking to clients’ businesses, attorneys can help build brands and experiences using the same strategies that ripened Apple from a small, scrappy underdog to one of the most successful and respected technology companies in history.

Trademarks and Trade Dress

Applying for trademark registrations is often one of the first items on the entrepreneur’s agenda. However, after filing trademark registration applications for the company’s name and logo, many attorneys and entrepreneurs fail to take the additional steps required to actually develop a brand.

Intellectual property attorneys are well aware that proper branding requires ensuring, among other things, that the marks are sufficiently distinctive, do not infringe the rights of third parties, are properly safeguarded with adequate quality control protections, and that policies are in place to protect domain names and online marks. However, many attorneys and entrepreneurs fail to appreciate that brand development is a larger process that requires intangible considerations as well.

Websites, product packaging, stationery, business cards, and marketing materials should speak with one voice. Logos, slogans, color schemes, and typefaces should complement one another and be used consistently.

Entrepreneurs should find a talented graphic designer to create a brand that conveys a specific message to the public. For example, an accounting firm may use subtle colors and formal serif typefaces in order to convey an air of sophistication and professionalism to prospective clients. On the other hand, a cutting-edge Internet company vying for a slice of the millennial generation’s business may choose brighter colors, edgy graphics, and an informal sans serif typeface in order to appear young and current. Of course, the opposite may also be true—the accounting firm may want to appear hipper or target a younger clientele, and the Internet start-up may see opportunity in those who are seemingly averse to technology.

Knowledge of design thinking is important for lawyers because a company’s design elements, taken together as a whole, may be protected under federal law as trade dress. “The concept of ‘trade dress’… refers to the total image of a product and may include features such as size, shape, color, color combinations, texture or graphics.”[2] Courts have recognized and protected as trade dress the overall layout of the business, interior color, color of employee uniforms, logos, and point of purchase materials and displays as elements of the plaintiff’s trade dress. [3]

Steve Jobs’ Obsession to Detail

Steve Jobs’ meticulous attention to detail was a driving force in the design and trade dress of Apple products. In an article[4] introducing Walter Isaacson’s new biography of Jobs, Malcolm Gladwell observed that Jobs was more of a “tweaker” than an actual inventor. Jobs was a perfectionist, and would drive his designers crazy tweaking and modifying designs. For even seemingly minute details, such as the title bars at the top of windows and documents, Jobs obsessed.

“He forced the developers to do another version, and then another, about twenty iterations in all, insisting on one tiny tweak after another, and when the developers protested that they had better things to do he shouted, ‘Can you imagine looking at that every day? It’s not just a little thing. It’s something we have to do right.’”

It was Jobs’ overly obsessive personality that dictated every design detail of every Apple product.

Apple’s branding succeeded in uniting seemingly unrelated products, thereby creating an integrated experience for the consumer. When you enter an Apple Store, you may notice the clean appearance, the white, black, and sky-blue color scheme and unfinished wooden tables. You may also notice the layout of the products in close proximity to one another, with consistently designed labels using the same colors and typefaces. Apple uses typefaces and colors consistently throughout its online and physical stores. One particularly clever marketing technique is the placement and use of Apple products to market a completely different item. Next to MacBook Pro® computers are iPad®s displaying the MacBook Pro’s specifications, allowing the customer to simultaneously (1) explore and touch the MacBook Pro itself, (2) read and learn about the MacBook Pro on the iPad, and (3) become familiar with the ease and feel of the iPad. This is a perfect example of Apple’s ability to put the consumer’s experience first and to leave no doubt that the consumer will form a bond with the technology.

Another useful tool under trademark law is creating a family of trademarks, which Apple accomplished with its “MAC” and “i”-related products. Courts have defined a “family of marks” as “a group of marks having a recognizable common characteristic, wherein the marks are composed and used in such a way that the public associates not only the individual marks, but the common characteristic of the family, with the trademark owner.”[5]

While consumers have certainly heard of the iPhone®, iMac®, iPod®, and iPad, they may be less familiar with iChat®, iWork®, and iLife®, some of Apple’s software products. When consumers see a lowercase “i” these days, they expect to see an Apple product and all that goes with it. Even among diverse Apple products, the “i” prefix creates an additional layer of protection and allows Apple to preclude third parties from using the same prefix for confusingly similar goods and services, even if the “i” is not itself registered. The infringing mark would be analyzed under the same “likelihood of confusion” test as a traditional trademark infringement action.[6]

It is important to note, however, that families of marks are not easily created, and courts will not always recognize families of marks.[7]

Apple Sued Multiple Times for Trademark Infringement

Despite Apple’s obvious success in branding, it has found itself as the defendant in numerous trademark infringement actions. When Apple introduced the iPhone in 2007, Cisco Systems, which had already registered the mark “iPhone” with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, sued Apple. The case was settled out of court. When Apple released its “iCloud” cloud computing service in 2011, Apple was hit with a lawsuit from none other than I Cloud Communications LLC.[8] However, as a result of good lawyering on the part of Apple, I Cloud dropped the lawsuit and changed its name to Clear Digital Communications. Even as early as 1978, Apple invited trademark infringement lawsuits. Apple Corps, the holding company for the Beatles’ record label, Apple Records, has filed numerous lawsuits against Apple over the years for trademark infringement and subsequently for breaches of the parties’ settlement agreements (for, among other things, Apple’s branching out into the music business with its release of iTunes).

Copyright

Entrepreneurs must also have a basic understanding of copyright law. While this goes without saying for artists and entertainment-related businesses, the same holds true for all businesses. Entrepreneurs need attorneys who recognize copyright issues in the ordinary course of business in order to protect the company from infringement liability, while simultaneously safeguarding the company’s own copyrights.

Before using a copyrighted work, you must obtain full ownership through assignment, or, at minimum, by licensing the work from the proper owner for the intended purpose. This situation frequently arises when using a third party’s photos or text to build a website, post on a blog, or create marketing and advertising material.

Start-up companies and established businesses alike also must exercise caution when hiring independent contractors. The business will not automatically own the copyright for a work created by an independent contractor except in very limited circumstances—that is, for certain types of specially commissioned works if memorialized in writing as a “work made for hire.” For example, if you hire a photographer to photograph your employees for your company’s website, the photographer will own the copyright to those pictures, unless the photographer signs an assignment or license agreement transferring rights to you. (The photographer may still need to obtain model releases.) This is true even if you have entered into an agreement providing that the photographs are “works made for hire” because photographs do not fall within one of the enumerated types of “works made for hire” included in the Copyright Act.

Copyright Controversy Skyrockets with Rise of Internet

The 1990s saw the rise of the Internet and, with it, exponentially more complex legal questions. Many issues, particularly relating to online piracy, remain contentious and controversial, as evidenced by the Protect IP and Stop Online Piracy Acts, which recently stalled in Congress.

Back in 1998, Congress enacted the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) to address some of the issues. As intellectual property practitioners already know, the DMCA, among other things, increased penalties for Internet-based copyright infringement and criminalized certain acts, such as attempts to circumvent digital rights management technology (DRM) that protects copyrighted works from being copied. DRM is the reason why some digital files, such as music and movies, cannot be copied or placed on multiple devices (without sabotaging the DRM technology itself—also criminalized by the DMCA).

Steve Jobs strongly opposed DRM restrictions, and in 2007 he actually wrote a letter to the four largest record companies requesting that they abandon DRM technology entirely. Jobs argued “DRMs haven’t worked, and may never work, to halt music piracy.” Jobs felt that the record labels’ business model for the music industry was no longer sustainable and believed that convincing the music industry “to license their music to Apple and others DRM-free will create a truly interoperable music marketplace.”

Tech companies and software developers additional copyright concerns. “Computer programs” are specifically protected under the Copyright Act, which is the basis for why companies continually struggle with software piracy issues. The general rule is that one cannot reproduce a copyright owner’s work without permission. However, the “first-sale doctrine” limits the copyright owner’s rights by providing that, once a work is sold for the first time, the purchaser may then resell that lawfully obtained copy to a third party without permission from the owner. This is where it begins to get tricky. Most software developers provide, in pop-up windows that are rarely read by consumers (you usually just click “Agree”), that the software sold to the consumer is licensed, not purchased, with significant restrictions on its use and transferability.

This issue was litigated recently by Apple.[9] In that case, Apple successfully argued that its license agreement required its Mac OS X operating system to be used only on Apple computers. In reaching its decision, the court stated, “a software user is a licensee rather than an owner of a copy where the copyright owner (1) specifies that the user is granted a license; (2) significantly restricts the user’s ability to transfer the software; and (3) imposes notable use restrictions.”[10]

Although there is plenty of controversy as to whether or not software should be freely transferable after a lawful first purchase, the license agreement is an effective method, at least in some jurisdictions, to restrict the resale of software. Apple’s successful enforcement of its software license agreement serves as a reminder that computer companies, mobile app developers, and other technology based companies should ensure that they have properly protected their copyrights from unwanted reproduction through conspicuous and restrictive end-user license agreements.

Trade Secrets: Protection of Valuable Information

Trade secret issues arise in most commercial contexts, not only when literally protecting a secret formula or recipe.[11] Effective protection of trade secrets, as with other intellectual property, forces competitors to continuously innovate in order to maintain relevance with the public and gives companies a vehicle for fighting misappropriation of their property.

Whether information constitutes a trade secret depends, among other things, on the extent to which the company invests in its development, the steps taken to maintain its secrecy, and the justification for protecting the information from disclosure.[12] If a court determines that such information is a trade secret, it will then analyze whether or not it was improperly disclosed. The more stringent the steps taken to maintain secrecy, the more likely a court will agree that the secret was obtained improperly.[13]

One common method for protecting trade secrets is through noncompetition and nondisclosure provisions. Whether these provisions are independent agreements or part of an employment contract, they are useful tools for limiting the exposure of business secrets. Noncompetition and confidentiality provisions should be carefully drafted to limit employees’ ability to disclose trade secrets obtained from their employer. Noncompetition agreements must be limited in time and geographic scope (the extent to which such limitations are lawful depends on the area of expertise and jurisdiction), whereas confidentiality agreements may be broader. Even when noncompetition provisions are in place, a departing employee may work for a competitor if substantial efforts are taken to ensure that no trade secrets are disclosed to the new employer.[14]

Attorneys and entrepreneurs may also use trade secrets strategically in marketing. Apple was extremely careful in controlling its message through secrecy. By releasing a few small details but maintaining high levels of secrecy for upcoming products, Apple generated a huge amount of anticipation across the world ahead of each release. Even Apple’s worst kept secrets, such as details of new iPhone models, are vague enough to generate huge publicity prior to their release.

Innovations and Design

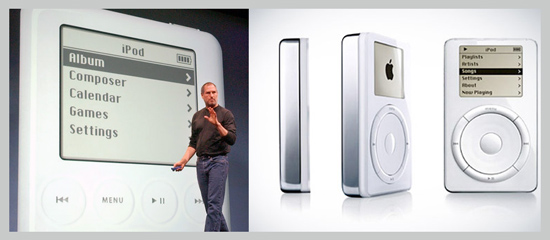

Constant innovation—whether in the form of a patentable invention or figuring out a more effective way to do a simple task—is the heart of a growing company and requires design thinking. In 2003, the New York Times interviewed Steve Jobs, two years after the release of the first iPod.[15] The journalist noted that Apple had released the iPod with a $400 price tag, even though it faced direct competition in the marketplace from a number of other digital music players.

How did the iPod become the best-selling digital music player and revolutionize portable music when it was far more expensive than similar products in the market? One reason for the success of the iPod surely was its design—but not just the iPod’s sleek look, although that was also a factor. Design refers to more than a modern and novel appearance. As Jobs explained to the New York Times, design is “not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.” Indeed, Apple has enjoyed its success not only because its products look good, but because its products work seamlessly, both alone and in harmony with one another.

Steve Jobs also understood the importance of quality over quantity. When he returned to Apple from Pixar in the 1990s, one way he reformed the company was by slashing the number of products being developed and focusing on a select few. This change enabled the company to trim the fat by channeling its resources to only the best ideas and eliminating the rest. However, even with Apple’s focus on the best ideas, Steve Jobs still managed to amass 317 patents listing him as one of the primary inventors.[16] These inventions include everything from the original computer frame that housed the first Macintosh to power adapters to new versions of Mac OS.

Entrepreneurs and innovators, and even attorneys, must learn how to “Think Different.” This famous Apple slogan was not only a memorable tagline, but Jobs’ message about the importance of thinking outside of the box. As Gladwell observed, “Jobs insisted that he wanted ‘different’ to be used as a noun … ‘It’s grammatical, if you think about what we’re trying to say. It’s not think the same, it’s think different. Think a little different, think a lot different, think different. “Think differently” wouldn’t hit the meaning for me.’”[17]

Steve Jobs left us with many lessons—on business, marketing, technology, and how to live a fulfilling life in the face of death. But his lessons in intellectual property may well have passed you by, even though they are an integral part of the success of every Apple product and service. Whether a business is building itself from the ground up, reforming itself to become more competitive in an overcrowded marketplace, or simply looking to protect one little idea that just might turn out to be the next paradigm shift in its class, lawyers and entrepreneurs alike should take a bite of the Apple and understand how to use intellectual property to protect and enforce creativity in business to the fullest extent possible.

Michael J. Zussman is a corporate and intellectual property law attorney in New York, N.Y., who works primarily with small businesses, technology-based companies, artists, and entrepreneurs. He is the Events chair and Younger Lawyers Division chair for the Federal Bar Association’s Southern District of New York Chapter. Michael may be reached at [email protected]. © 2012 Michael J. Zussman. All rights reserved.

Michael J. Zussman is a corporate and intellectual property law attorney in New York, N.Y., who works primarily with small businesses, technology-based companies, artists, and entrepreneurs. He is the Events chair and Younger Lawyers Division chair for the Federal Bar Association’s Southern District of New York Chapter. Michael may be reached at [email protected]. © 2012 Michael J. Zussman. All rights reserved.[1] Tim Brown, Definitions of Design Thinking, Design Thinking (Sept. 8, 2008), available at designthinking.ideo.com/?p=49.