Say What??? Campaigns that Failed to Translate

WANT TO SEE MORE LIKE THIS?

Sign up to receive an alert for our latest articles on design and stuff that makes you go "Hmmm?"

When a company decides to expand into global markets, their success depends on how well their brand is received by customers in each market. But as too many companies have learned the hard way, executing cross-cultural campaigns is not as easy as literally translating text from one language to the next.

It is important to consider cultural values, norms, etiquette, humor and slang when establishing a brand presence for international audiences. The process will likely take some time, considerable research and additional resources, but global markets are becoming increasingly crucial as growth opportunities emerge in developing countries.

Just because a product campaign is wildly successful in one country, does not guarantee it will transcend with global markets. Without the assistance of a qualified, culturally aware team, it’s challenging to recreate a message that feels authentic and resonates with a foreign audience. Even worse—a global campaign can go as far to offend the new market.

Whether these “miscommunications” are attributed to carelessness, cultural unawareness or lack of finances, they can have damaging consequences on the brand and the agency that failed to exercise its due diligence. Below, we recap some of the biggest translation blunders in marketing history, which in hindsight, could have easily been avoided.

Before we mock the slip-ups of some of the world’s most successful brands, we should mention that the validity of most these blunders are hearsay. While some cannot be proven, these stories are classic examples of how failed translation can be detrimental to a brand’s reputation.

1. Pepsi

When Pepsi entered the Chinese market, the translation of their slogan “Pepsi Brings you Back to Life” was a little more literal than they intended. In Chinese, the slogan meant, “Pepsi Brings Your Ancestors Back from the Grave.” I’ve heard a lot of faulty brand promises out there, but this one tops the list.

Source

2. California Milk Advisory Board

The California Milk Advisory Board experienced tremendous success with their “Got Milk?” campaign created by Goodby, Silverstein & Partners. But when the campaign was extended to Mexico, the Spanish version was interpreted, “Are you lactating?” The translation was offensive to the Latino market, as the idea of a Latina mother running out of milk is not a laughing matter. Fortunately, the disconnect between “Got Milk?” and Latino consumers was detected early.

Source

3. Puffs

Puffs tissues faced unforeseen challenges entering the German market, as the term “puff” is the common term for a whorehouse in Germany. The brand name also prompted negative responses from the British market, as “puff” is a highly derogatory term for homosexual.

4. Ford

When Ford introduced the Pinto in Brazil, they were confused as to why sales were going nowhere. The company later learned “Pinto” is slang for “tiny male genitals” in Brazil. Ford ultimately changed the car’s name to Corcel, which means ‘horse’ in Portuguese.

Source

5. Kentucky Fried Chicken

When Kentucky Fried Chicken first opened stores in China, it didn’t take long before they discovered their slogan, “finger lickin’ good” translated to “eat your fingers off.”

6. Schweppes

In Italy, a campaign for “Schweppes Tonic Water” translated the name into the much less thirst quenching “Schweppes Toilet Water.”

7. Coors

When Coors translated its slogan, “Turn it loose” into Spanish, it was read as “Suffer from diarrhea.”

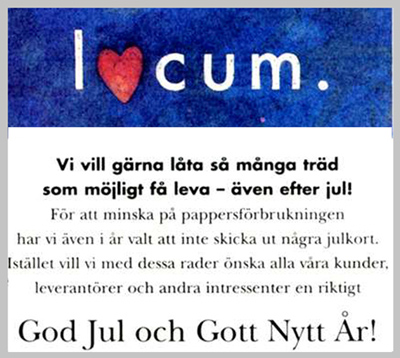

8. Locum

In 1991, Locum, a Swedish property management company, sent out Christmas cards to customers. They decided to give their logo a little holiday spirit by replacing the “o” in Locum with a heart. We don’t need to spell it out for you, but some of its recipients could have misinterpreted the message.

9. Orange

During its 1994 launch campaign, the telecom company Orange had to change its ads in Northern Ireland. Their successful campaign slogan was, “The future’s bright … the future’s Orange.” However, in the North the term “Orange” is linked to the Orange Order, the Protestant organization (viewed by many Catholics as both sectarian and hostile). The implied message that the future is bright, the future is Protestant, loyalist… didn’t resonate with the Catholic Irish population.

Source

10. GEC-Plessey Telecommunications

In 1988, the General Electric Company (GEC) and Plessey combined to create a new telecommunications giant. This merger required a brand name that evoked technology and innovation. The winning proposal was GPT for GEC-Plessey Telecommunications. The French population interpreted the new name a bit differently, as GPT is pronounced in French as “J’ai pété” or “I’ve farted.”

11. Honda

Car producer Honda decided to keep the name ‘Fitta’ when they introduced the car in Sweden. They later learned, “fitta” was an old word used in vulgar language to refer to a woman’s genitals in Swedish, Norwegian and Danish. The Honda Fitta is now sold in Sweden with the name of Honda Jazz.

12. Pepsodent

Pepsodent tried to sell its toothpaste in Southeast Asia by emphasizing that it “whitens your teeth.” This product “benefit” did not resonate with the target audience considering the local natives chew betel nuts to blacken their teeth, which they find attractive.

Source

13. Braniff Airlines

In 1977, Braniff Airlines ran ads on television and radio, publicizing the leather seats they’d installed in First Class, with the slogan, “Fly in leather.” This was translated for Spanish-speaking markets as, “Vuela en cuero.” But, when spoken, “en cuero,” or “in leather” sounds identical to “en cueros,” which means “naked” when spoken quickly. In effect, Braniff advertised its slogan as “Fly naked.”

The Notorious Nova

The most famous story of international marketing blunders is that of Chevy’s Nova car marketed in Latin America. Since the car’s name, “No va” literally means, “It doesn’t go” in Spanish, the tale explains how Latin American car buyers shunned the car, forcing Chevrolet to pull it from the market. However, what the textbooks and thousands of references to this tale on the Internet fail to mention is that, it never happened.

Though the Chevy Nova story may not be true, it continues to live on as a classic example of how cultural awareness plays a vital role in the success (or failure) to adapting a campaign for foreign markets.

If you found this blog entertaining, check out our collection of Embarrassing Design Blunders here.